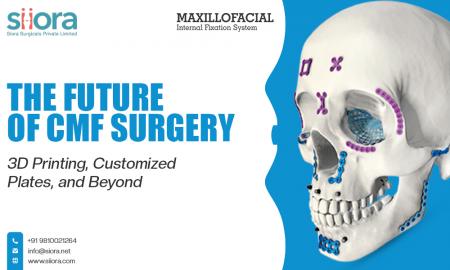

The future of craniomaxillofacial (CMF) surgery is being shaped less on the instrument tray and more on the planning screen. 3D printing, customized plates, and digital workflows are quietly turning “routine” facial surgery into something far more precise, predictable, and patient specific.

From generic plates to planned solutions

For a long time, CMF surgery revolved around standard plates and screws bent by hand on the back table. Surgeons learned to improvise: contouring straight plates to curved mandibles, trimming meshes for orbital floors, and adjusting fixation on the fly. It worked, but it came at a cost—longer operative times, variable accuracy, and a lot of reliance on experience and “good hands.”

Digital planning and 3D printing are changing that dynamic. Instead of shaping the hardware around the fracture or deformity during surgery, surgeons now plan the reconstruction virtually before anyone scrubs in. Bone cuts, movements, and plate positions are mapped out on a 3D model, then translated into guides and customized maxillofacial implants that bring the virtual plan into the real operating room.

3D printing as the new workhorse

In CMF, 3D printing started with simple models. Surgeons would print skulls and mandibles from CT scans to understand complex fractures, congenital deformities, or tumor defects. That alone made a difference—holding the anatomy in your hands before surgery beats scrolling through axial cuts on a screen any day.

The real step forward came when printing moved from models to tools and implants. Today, 3D printers are used to create cutting guides, drilling guides, and even patient-specific titanium plates. These guides help reproduce planned osteotomies and screw positions with a level of consistency that is difficult to match freehand. For the surgeon, that means less guesswork; for the patient, it often means better symmetry, occlusion, and overall aesthetics.

Customized plates and patient-specific implants

Customized plates are the natural extension of virtual planning. Instead of taking a generic plate and bending it to fit an irregular mandible or midface, engineers design a plate that already matches the planned bony contour. Screw holes line up with safe bone corridors, plate thickness is tailored to the load and location, and the design can even integrate features like hook extensions or slots for soft-tissue suspension.

In tumor surgery and secondary deformity correction, this customization is especially powerful. Jaws resected for cancer or heavily distorted by old trauma rarely resemble “standard” anatomy. A patient-specific plate, often combined with a fibula or iliac crest graft, can restore both function and facial contour far more predictably than ad hoc solutions. In orthognathic surgery, custom plates and guides help lock planned maxillary and mandibular movements into place, reducing the back-and-forth adjustments that used to eat up operative time.

Beyond titanium: new materials and biologic thinking

While titanium will remain central, the future of CMF implants is not purely metallic. Bioresorbable polymers, magnesium-based alloys, and composite materials are being explored for applications where long-term hardware may be undesirable, such as pediatric cases or areas with high infection risk. The idea is simple: provide enough rigidity while the bone heals, then gradually fade away as the body takes over.

Alongside these materials, there is growing interest in integrating biologics and regenerative strategies. 3D-printed scaffolds seeded with bone-forming cells or growth factors, porous titanium structures designed to encourage bone ingrowth, and hybrid constructs that blend fixation with regeneration are all being studied. The end goal is not just to hold bone still, but to actively support its healing and remodeling in a more natural way.

Smarter planning with AI and data

Digital planning generates a huge amount of data: preoperative scans, virtual simulations, intraoperative navigation logs, and postoperative outcomes. Over time, this creates a rich feedback loop that can guide better decisions. Machine learning tools are starting to assist with tasks like automatic segmentation of CT data, prediction of ideal plate designs, or suggesting optimal repositioning in orthognathic cases.

For CMF teams, this means planning can become faster and more standardized without losing the nuance that experienced surgeons bring. Instead of starting from scratch each time, future software may offer evidence-based templates that can be adapted to the individual patient, blending population data with personalization.

What does this mean for surgeons and patients?

For surgeons, the shift toward 3D printing and customized plates changes where effort is spent. More work moves to the preoperative phase—discussing plans with engineers, reviewing virtual models, refining osteotomy lines—so the operation itself becomes more about execution than improvisation. Training will have to adapt, with residents learning digital workflows alongside classic plating skills.

For patients, the upside is straightforward: better fit, better symmetry, fewer surprises. When bones are moved or reconstructed according to a carefully tested virtual plan and fixed with orthopedic implants designed for that exact geometry, there is a higher chance of achieving both functional and aesthetic goals in a single operation. As costs come down and access improves, these technologies are likely to move from elite centers into everyday CMF practice.

In the end, It is about giving skilled teams sharper tools—virtual planning, 3D printing, customized plates, smarter materials—so that each face is treated not as a variation of a template, but as a unique structure with its own demands and possibilities.

Comments (0)